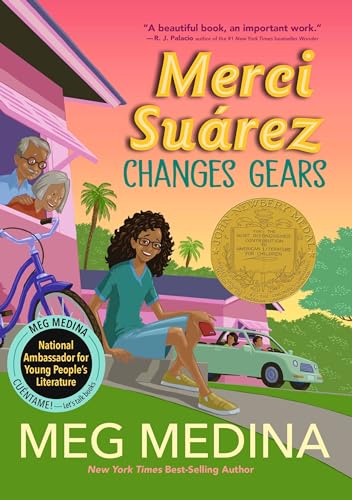

Merci Suárez Changes Gears - Hardcover

Thoughtful, strong-willed sixth-grader Merci Suarez navigates difficult changes with friends, family, and everyone in between in a resonant new novel from Meg Medina.

Merci Suarez knew that sixth grade would be different, but she had no idea just how different. For starters, Merci has never been like the other kids at her private school in Florida, because she and her older brother, Roli, are scholarship students. They don’t have a big house or a fancy boat, and they have to do extra community service to make up for their free tuition. So when bossy Edna Santos sets her sights on the new boy who happens to be Merci’s school-assigned Sunshine Buddy, Merci becomes the target of Edna’s jealousy. Things aren't going well at home, either: Merci’s grandfather and most trusted ally, Lolo, has been acting strangely lately — forgetting important things, falling from his bike, and getting angry over nothing. No one in her family will tell Merci what's going on, so she’s left to her own worries, while also feeling all on her own at school. In a coming-of-age tale full of humor and wisdom, award-winning author Meg Medina gets to the heart of the confusion and constant change that defines middle school — and the steadfast connection that defines family.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

We’re only halfway through health and PE when he adjusts his tight collar and says, “Time to go.”

I stand up and push in my chair, like we’re always supposed to, grateful that picture day means that class ends early. At least we won’t have to start reading the first chap-ter in the textbook: “I’m OK, You’re OK: On Differences as We Develop.”

“Coming, Miss Suárez?” he asks me as he flips off the lights.

That’s when I realize I’m the only one still waiting for him to tell us to line up. Everyone else has already headed out the door.

This is sixth grade, so there won’t be one of the PTA moms walking us down to the photographer. Last year, our escort pumped us up by gushing the whole way about how handsome and beautiful we all looked on the first day of school, which was a stretch since a few of us had mouthfuls of braces or big gaps between our front teeth.

But that’s over now. Here at Seaward Pines Academy, sixth-graders don’t have the same teacher all day, like Miss Miller in the fifth grade. Now we have homerooms and lockers. We switch classes. We can finally try out for sports teams.

And we know how to get ourselves down to picture day just fine — or at least the rest of my class does. I grab my new book bag and hurry out to join the others.

It’s a wall of heat out here. It won’t be a far walk, but August in Florida is brutal, so it doesn’t take long for my glasses to fog up and the curls at my temples to spring into tight coils. I try my best to stick to the shade near the building, but it’s hopeless. The slate path that winds to the front of the gym cuts right across the quad, where there’s not a single scrawny palm tree to shield us. It makes me wish we had one of those thatch-roof walkways that my grandfather Lolo can build out of fronds.

“How do I look?” someone asks.

I dry my lenses on my shirttail and glance over. We’re all in the same uniform, but some of the girls got special hairdos for the occasion, I notice. A few were even flat-ironed; you can tell from the little burns on their necks. Too bad they don’t have some of my curls. Not that everyone appreciates them, of course. Last year, a kid named Dillon said I look like a lion, which was fine with me, since I love those big cats. Mami is always nagging me about keeping it out of my eyes, but she doesn’t know that hid-ing behind it is the best part. This morning, she slapped a school- issue headband on me. All it’s done so far is give me a headache and make my glasses sit crooked.

“Hey,” I say. “It’s a broiler out here. I know a shortcut.”

The girls stop in a glob and look at me. The path I’m pointing to is clearly marked with a sign.

MAINTENANCE CREWS ONLY.

NO STUDENTS BEYOND THIS POINT.

No one in this crowd is much for breaking rules, but sweat is already beading above their glossed lips, so maybe they’ll be sensible. They’re looking to one another, but mostly to Edna Santos.

“Come on, Edna,” I say, deciding to go straight to the top. “It’s faster, and we’re melting out here.”

She frowns at me, considering the options. She may be a teacher’s pet, but I’ve seen Edna bend a rule or two. Making faces outside our classroom if she’s on a bathroom pass. Changing an answer for a friend when we’re self-checking a quiz. How much worse can this be?

I take a step closer. Is she taller than me now? I pull back my shoulders just in case. She looks older somehow than she did in June, when we were in the same class. Maybe it’s the blush on her cheeks or the mascara that’s making little raccoon circles under her eyes? I try not to stare and just go for the big guns.

“You want to look sweaty in your picture?” I say.

Cha- ching.

In no time, I’m leading the pack of us along the gravel path. We cross the maintenance parking lot, dodging debris. Back here is where Seaward hides the riding mow-ers and all the other untidy equipment they need to make the campus look like the brochures. Papi and I parked here last summer when we did some painting as a trade for our book fees. I don’t tell anyone that, though, because Mami says it’s “a private matter.” But mostly, I keep quiet because I’m trying to erase the memory. Seaward’s gym is ginormous, so it took us three whole days to paint it. Plus, our school colors are fire- engine red and gray. You know what happens when you stare at bright red too long? You start to see green balls in front of your eyes every time you look away. Hmpf. Try doing detail work in that blinded condition. For all that, the school should give me and my brother, Roli, a whole library, not just a few measly text-books. Papi had other ideas, of course. “Do a good job in here,” he insisted, “so they know we’re serious people.” I hate when he says that. Do people think we’re clowns? It’s like we’ve always got to prove something.

Anyway, we make it to the gym in half the time. The back door is propped open, the way I knew it would be. The head custodian keeps a milk crate jammed in the door frame so he can read his paper in peace when no one’s looking.

“This way,” I say, using my take-charge voice. I’ve been trying to perfect it, since it’s never too early to work on your corporate leadership skills, according to the manual Papi got in the mail from the chamber of commerce, along with the what- to- do- in- a-hurricane guidelines.

So far, it’s working. I walk us along back rooms and even past the boys’ locker room, which smells like bleach and dirty socks. When we reach a set of double doors, I pull them open proudly. I’ve saved us all from that awful trudge through the heat.

“Ta- da,” I say.

Unfortunately, as soon as we step inside, it’s obvious that I’ve landed us all in hostile territory.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCandlewick

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 076369049X

- ISBN 13 9780763690496

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Merci Suárez Changes Gears

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 076369049X-11-27024697

Merci Sußrez Changes Gears

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9780763690496

Merci Suárez Changes Gears by Medina, Meg [Hardcover ]

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780763690496

Merci Su�rez Changes Gears (Hardback or Cased Book)

Book Description Hardback or Cased Book. Condition: New. Merci Su�rez Changes Gears 1.1. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780763690496

Merci Suárez Changes Gears Format: Hardcover

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 076369049X

Merci Suárez Changes Gears

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # 076369049X

Merci Suárez Changes Gears

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk076369049Xxvz189zvxnew

Merci Suárez Changes Gears

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-076369049X-new

Merci Suárez Changes Gears

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190165947

Merci Suarez Changes Gears

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 30705455-n